Ok. I confess, this was a trick question. The bell is not presently in Dedham, but it did hang in the belfry of the First Baptist Church on Milton Street for over 90 years. Congrats to Robert Morrissey for figuring out the location of the bell. If you want to see the bell in person, you’ll have to take a road trip to Falmouth, where it has resided for over 50 years. The journey of this historic bell from East Dedham to a private garden almost 60 miles away is an interesting and somewhat delicate subject.

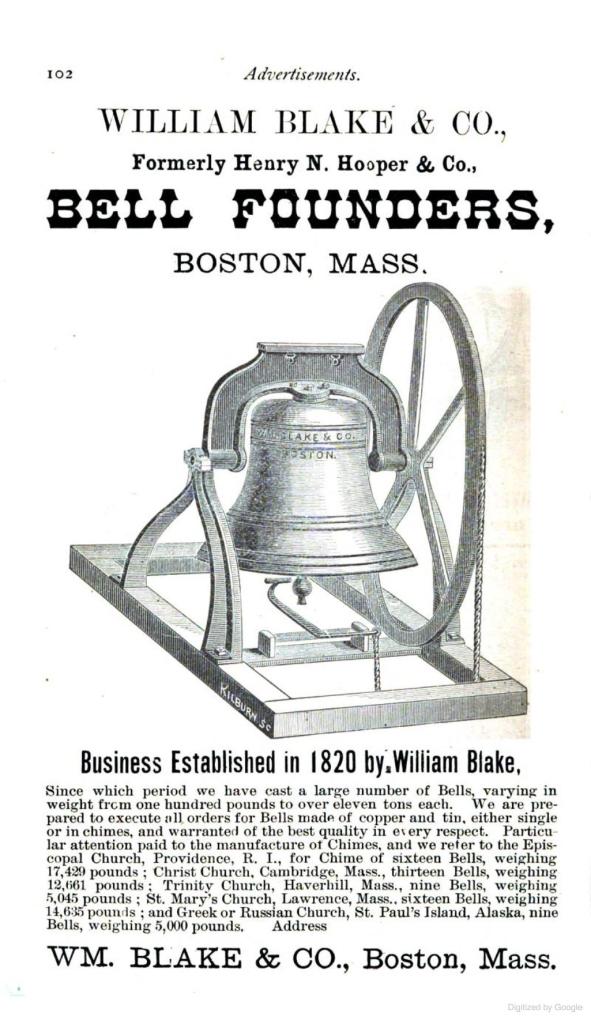

The East Dedham Baptist Church was officially established in 1843, and in 1852 a new wooden church was built at the corner of Myrtle and Milton Streets. Through the generosity of Jonathan Mann of Canton, a 2000 lb. bell was cast in Boston by the William Blake Company and presented to the congregation on February 20, 1882. The church underwent renovations in 1910 and a belfry was built to house the bell, which would hang there for the next 62 years. In 1919 the church was renamed the First Baptist Church.

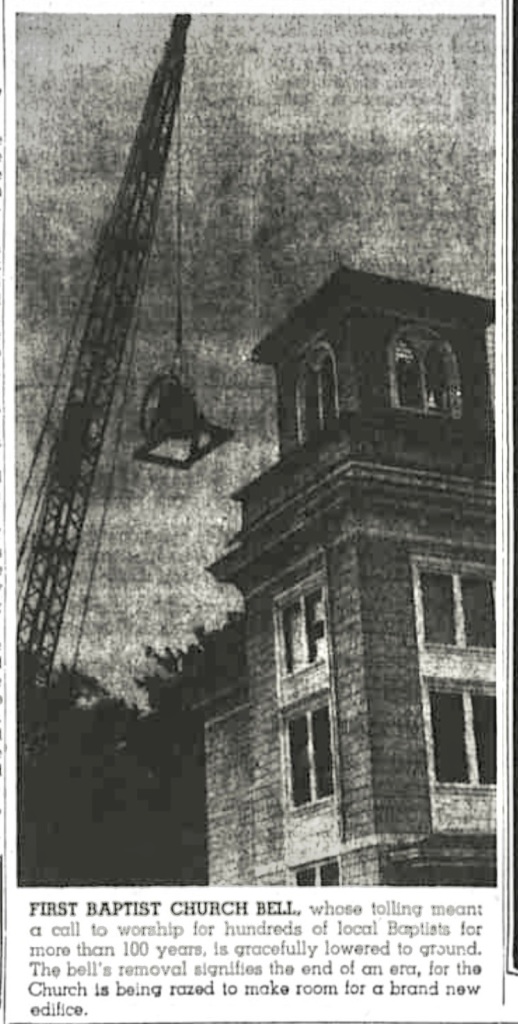

By 1972, time had taken its toll on the wooden structure, and church leaders determined that the building would have to be torn town completely and replaced. The demolition took place in August, coincidentally the same summer that the famed Avery Oak came down in a storm. Demolition was done by the John J. Duane Wrecking Company of Quincy.

Here’s where the bell makes its mysterious departure from old Shiretown. According to church sources, the congregation, being in tough financial straits, offered the bell to the demolition company as partial payment. Meanwhile, husband and wife Charlie and Margaret Spohr were living on six beautiful acres in Quissett, a village in Falmouth. For decades the Spohrs had been transforming their property alongside Oyster Pond into a series of unique and lush gardens; Margaret tending to the plantings, Charlie taking care of the “decorations.” which included millstones, chains, anchors, (75 of them!), lanterns and…bells. When the Duane Company offered to sell the bell to Charlie, he enthusiastically accepted and made it a prized feature of his collection.

Back in Dedham, a new church was built and dedicated on September 30, 1973, and stands there to this day. In 1994 the congregation voted to change its name to the Fellowship Bible Church, and a diverse community of believers continues to carry out the mission of the church.

Upon the death of Margaret Spohr in 2001 (Charlie passed away in 1997), the property was left to the Charles and Margaret Spohr Charitable Trust which maintains the gardens and welcomes visitors free of charge all year. In 2005, church pastor Dr. Omar Adams wrote to the trust requesting that the bell be returned, or offered for sale. In the letter, Adams expressed the desire to celebrate the church’s 160 year history in Dedham, and hoped it could be returned in time for the dedication of an addition to the 1973 building. That did not happen, and the bell can still be found on the grounds of the Spohr Gardens.

While the current church administration holds no ill feelings to Spohr Gardens, they do feel a connection to the bell and would welcome an opportunity to display it on church grounds. In the meantime the bell can be seen in its beautiful garden setting in Falmouth. Here is a link to their website where you can plan your trip and find out more information about this unique Cape Cod destination.